Today, Valentine’s Day, is two years and five months since my mother’s journey with Alzheimer’s reached its destination on September 14, 2017. A lot has happened over the past 897 days. I think it took me this long to complete the grieving process, if there is such a concept. I feel that way because I can now reflect on the nine years that I walked alongside her, on an often-heartbreaking journey. I see more clearly the way points, the forks-in-the-road, the lessons at each turn begging me to learn, and so many opportunities to share inspiration and practical guidance for the thousands of other daughters and families on a similar journey.

My hope is that by sharing these reflections, you or someone you know may walk your own journey a little lighter, with an open heart and open mind.

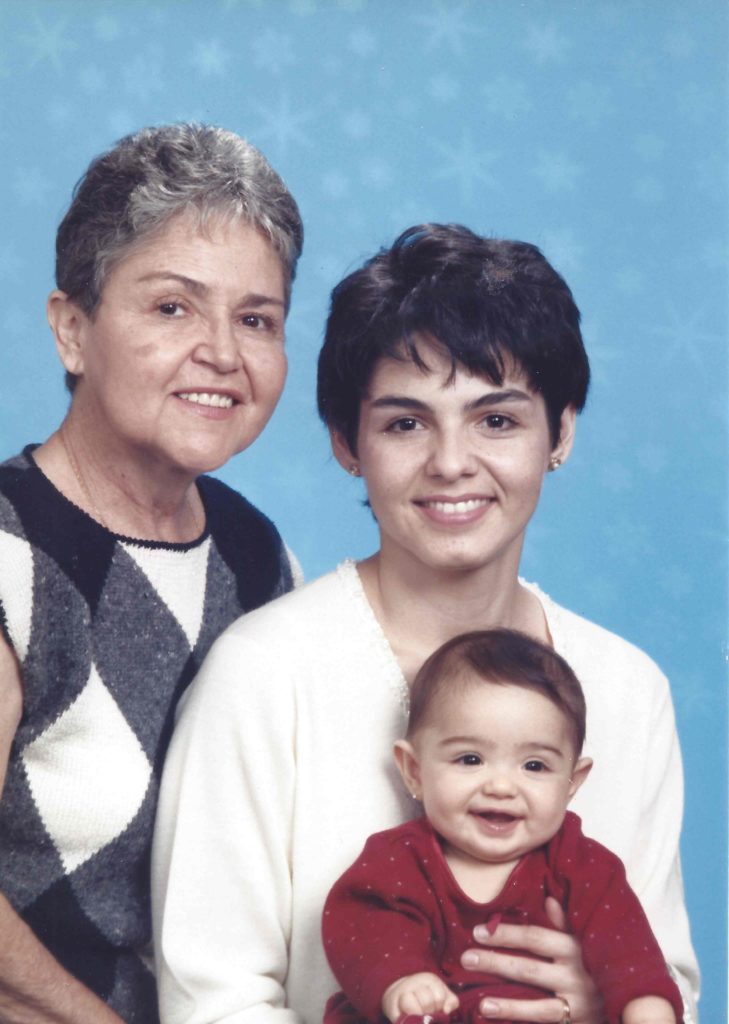

I began to notice the warning signs of my mother’s changing cognitive function by the time my daughter was in fourth grade (isn’t it funny how the milestones of your loved ones become your references points?). Unfortunately, I did not always immediately follow through after observing these signs. Not surprisingly, forgetfulness, something most people discover more and more with each passing year, was one of the first signs. Forgetting events, conversations, and recent tasks (i.e. short-term memory recall) suddenly became the norm, rather than the exception. I remember the day when there was no longer room for denial of what was happening. I had coordinated with my mom to pick my daughter up from school and she got lost on her way, ending up at a different elementary school in a full panic because the school denied any knowledge about a student with my daughter’s name. When I arrived at the school to meet my mother and help get her reoriented, she was an absolute wreck, thinking that the school had “lost” my daughter or worse that she had somehow “lost her.” That day was eye-opening for me.

In hindsight, there were many barriers to acknowledging, and accepting, what was happening to my mother, rather than making simple excuses for her behavior. I have also learned, through other families, some of the barriers they faced along their journey.

- “Sandwich Generation” Effect. This effect has been described for those of us “sandwiched” between raising our children and caring for our aging parents, constantly juggling many competing demands. Time to “be present” is in short supply and it is the greatest barrier to families getting an early diagnosis and finding the resources and education to help keep their loved one safe.

- Nature of the Relationship. Valentine’s Day was always a favorite holiday for my mom. Each year, no matter how old I was, she would give me a sweet card or a little gift. I never doubted my mom’s love for me. She chose to give her whole life to me selflessly and unconditionally. I was the center of her universe and she would move mountains over the course of my life to ensure my health and well-being. While incredibly generous, the expectations that emerged set a very high bar for reciprocity that would play out over time and in acute ways in our relationship. The complicated nature of mother-daughter relationships sometimes causes wounds, and some heal better than others. I believe some of the healed, yet visible, scabs in my relationship with my mother delayed my acting on the signs that I was seeing because I was in a mode of “containment.” However, in setting those boundaries, I never foresaw that it would dull my awareness of exactly how her day-to-day routine was shifting because she was overcompensating for her deteriorating cognitive functions. I now know that the physiological changes she was undergoing may have benefited from early detection and treatment.

- Shifting Roles. My mom and I had always been “equal partners.” As a senior in high school, I entered the work-study program, so I could work full-time to help support our household, and this continued as I was worked my way through college. We always had a rhythm of working hard and supporting one another. Looking back, it was never a stated goal between us, but rather intuitively, we were always working toward getting our “heads above water.” As my career flourished and I was able to lighten her financial burdens, I assumed more of the household budget and expense responsibilities. She willingly accepted this help because she never really liked numbers and paperwork. Because this was our routine, I never saw the difficulty she was having in doing simple math or her ability to interpret information in writing.

- Financial Hardship. While, at this stage, managing my mom’s financial needs was not overly burdensome, I have learned since, from working with other families, the stress of living paycheck-to-paycheck and multiple jobs can be a huge barrier to families recognizing the early signs. It is very difficult to be present when you’re just struggling to make ends meet.

- Sibling Relationships. As an only child, I did not have any siblings with which to compare notes or share burdens. This sometimes can be the biggest barrier for families with multiple siblings, especially if any or all of them live far away from their loved one. I know it was hard enough for me to overcome barriers, overlay these same barriers times multiple siblings who have varying degrees of involvement with a parent (whether locally or from afar), and it can be the perfect storm for a cognitively impaired parent to “mask” their symptoms and “avoid” the conversations needed for proactive steps to be taken.

Inevitably, as I write this, I ask myself, if I could do it over again–What would I do differently? What would it have looked like had I followed through, as I was observing these signs? What can others learn from my experience? Below, is what I would urge you to consider:

- Ask for help. Living in the “sandwich generation” is a barrier outside of your control. However, how you recognize the situation and compensate for it, is within your control. Looking back, I could have asked my husband, my sister-in-law, and other close relatives to understand what was happening and see if they could help assume more of my child-care responsibilities. I could have taken a step back from some of my outside of work commitments, so I would have had more time to be present with my mom to better understand what was happening, as opposed to squeezing her in between commitments and other appointments and rushing around to do it all. Now, I know about the Alzheimer’s Association and the existence of support groups in the community to share experiences and resources. There is even a “Brain Bus” that goes around the state of Florida providing mobile services at community centers and events. I know that the need is great, and resources are scarce, but there are outlets, if you stop juggling your daily tasks long enough to look for them.

- Forgive and seek forgiveness. We all have wounds, some are healed, some are not. As I continue to work with families navigating how to help their loved one, it becomes more and more obvious that so much of the stress of making that transition is actually a reflection of old wounds. Hindsight has shown me that forgiving and asking for forgiveness is a first step that can open the other doors to trust. With trust, all is possible.

- Be present. There was a long time when I did not take a half an hour just to stop by my mom’s house for a cup of tea and conversation. I did not just call out of the blue to have a conversation about something other than a task, a to-do-list, or something else that was a priority in that moment. Taking her grocery shopping would have been “one more thing on my to do list,” but really, it would have shown me a lot to just walk the aisles with her and observe what she was picking out for her meals, or what she was not picking out. Being present requires us to stop rushing to truly be in the moment with our loved one. It is not easy. It requires us to prioritize our loved one over all the other things on our calendar and in our lives. And, it will be the most important effort to truly understanding and building trust with your loved one, as you walk this journey together.

- Dream together. Once I took the time to be present, I shifted the nature of my conversations from being task-oriented to being story-oriented. I would ask her countless questions: What did you dream of as a child? How did you envision your life? How do you want your family to remember you? What do you want me to do if you could no longer tell me what you wanted? What do you not want me to do if you could no longer communicate? What are you most happy about in your life now? What are you most afraid of? I wanted to keep the conversations as casual as possible, so I gathered these answers over many weeks and months. Over the course of that time, I started to formulate my “elevator speech.” This was the three- to five-minute message that captured the highlights of her aspirations, while acknowledging her fears. I would use this speech at opportune times to reinforce that I was hearing her wishes and, along the way, I would insert steps that could be a reflection of how we could work together, as we always had, to realize her dreams and keep her safe and well.

- Plan together. Ultimately, the decision to sell her home and move her to an assisted living facility was a mutual decision. Thankfully, there was no emergency hospitalization due to a fall or a doctor securing her fate to a facility. It was not easy, but over the course of a year, I forgave and asked for forgiveness. I was present and we dreamed and planned together. There would be many more challenges to come, but I know she had an infinitely better quality of life in the years following her official diagnosis.